Eileen Warburton’s biography, John Fowles: A Life in Two Worlds was published by Viking/Penguin (500 pages, $29.95) in 2004. It is available at Amazon.com (in the U.S.), Amazon.co.uk (in the United Kingdom) and wherever fine books are sold.

From the dust jacket flap:

Celebrated and applauded as one of the most seductive storytellers of the late twentieth century, a magician of the English language, a pioneer of postmodern sensibility, and the stylistic inspiration for a generation of writers and poets, John Fowles burst from obscurity in 1963 with the spectacular debut of his first novel, The Collector. Over the next two decades, the books rolled out: the astonishing psychological mystifications of The Magus, the haunting Victorian love story of The French Lieutenant’s Woman, the pithy existentialist philosophy of The Aristos, the poignant short stories of The Ebony Tower, the transforming memory journey of Daniel Martin, the sizzling parable of Mantissa, the seventeenth-century religious puzzle of A Maggot, and a host of flawless dramatic translations and penetrating essays. The appearance of each of Fowles’ romantic and fiercely intellectual works became a major literary event.

Yet John Fowles himself remained as much a mystery as the twists and turns of his most famous novels. Charming and urban but increasingly reclusive, he shunned the trappings of the celebrity world to withdraw into the solitude of a remote seaside home and the complex richness of his own imagination. Beyond his need for personal privacy, the secret he guarded was the extent to which his fiction was the mythologized tale of his own inward and outward life.

This story of Fowles’ life and its reflection in his work is told for the first time in this groundbreaking biography. Drawing on unprecedented access to sixty years of the writer’s unedited private diaries; to searching interviews with his family, friends, and associates; to his drafts and unpublished works; to Fowles’ intimate personal correspondence and a lifetime’s confessional letters by his first wife, Elizabeth, Eileen Warburton provides a richly detailed, authoritative portrait of the troubled and triumphant man who became one of the twentieth century’s most important writers.

She chronicles Fowles’ prewar childhood in a London commuter suburb and in wartime rural England, his Oxford education, his self-inventing wanderings through France and Greece, and his ambitious, impoverished apprentice years in London. She follows the powerful trajectory of Fowles’ long writing career, even as the famous artist evaded exposure and created escapes through his unpublished writings and retreats into the wild natural world. From his wife’s letters and often in Elizabeth Fowles’ own words, Warburton also presents with compelling sympathy Fowles’ tumultuous thirty-seven year love affair with the beloved woman who edited his work, connected him to other people, and inspired his most memorable female characters.

Brilliantly researched and written with a narrative immediacy worthy of its novelist subject, John Fowles: A Life in Two Worlds brings Fowles’ many readers a long-overdue perspective on the life of this enduring storyteller.

From KIRKUS REVIEWS, February 1, 2004:

Illuminating life of the author of such works as The Collector and The French Lieutenant’s Woman.

The “two worlds” of the subtitle could be subdivided, multiplied, and variously reassigned: John Fowles the country gentleman, the Hollywood bon vivant, the London sophisticate, the cosmopolitan philosopher, the archivist and preservationist of village green and Ica. For Warburton, who has enjoyed access to the famously private Fowles’ diaries and letters, the two worlds that matter are those of Fowles the living writer and Fowles the living person, and she does a fine job of capturing him in both guises. (For his part, Fowles has grumbled, “I know many writers fight fanatically to keep their published self separate from their private reality. . . But I’ve always thought of that as something out of our social, time-serving side; not our true artistic ones.”) On the ordinary-life side, she explores Fowles’ childhood and early adulthood, marked by illness and checkered episodes in boarding school and the military, as well as the influence of his wife, Elizabeth, to whom he was married for 37 years and who appears, if obliquely, in many of his works. On the literary side, Warburton ably charts the course of Fowles’ evolution as a writer, one who seems not to have sought recognition until he had practiced a long and exacting apprenticeship; by the time his first book, The Collector, was published in 1963, she tells us, Fowles had written and shelved “nine or ten other novels.” Those who aspire to a soft life of literary fame will find Fowles’ example salutary, for no sooner had he become celebrated than did Fowles begin to reject the world of cocktail parties and seminars—though not the money that came with the job, and especially not the money that came from Hollywood, which won him the “rather spectacular Georgian house” on the English Channel that served as the focal point for his later life and figured in many of his later books.

A hard-working life of a hard-working, justly honored writer: very well told.

Here are a few photos from the book:

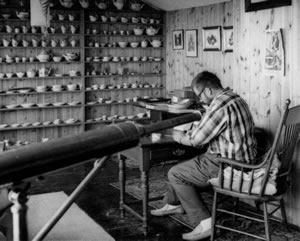

John Fowles at work in his writing room at Underhill Farm, Lyme Regis, Dorset, 1966-67. In this room he wrote The French Lieutenant’s Woman as well as the script for the film of The Magus. Note Fowles’s prized collection of New Hall china and the telescope for watching the sea, much as does Sarah Woodruff in The FLW.

John Fowles at work in his writing room at Underhill Farm, Lyme Regis, Dorset, 1966-67. In this room he wrote The French Lieutenant’s Woman as well as the script for the film of The Magus. Note Fowles’s prized collection of New Hall china and the telescope for watching the sea, much as does Sarah Woodruff in The FLW.

John Fowles and his editor and friend, the legendary Tom Maschler of Jonathan Cape, at Belmont house in Lyme Regis, Dorset, c. 1972. Fowles was the first author that Maschler published from his very first book, The Collector (1963). Maschler was the driving force behind the establishment of the Booker Prize and was associate producer of the film of The French Lieutenant’s Woman. Photo by Elizabeth Fowles.

John Fowles and his editor and friend, the legendary Tom Maschler of Jonathan Cape, at Belmont house in Lyme Regis, Dorset, c. 1972. Fowles was the first author that Maschler published from his very first book, The Collector (1963). Maschler was the driving force behind the establishment of the Booker Prize and was associate producer of the film of The French Lieutenant’s Woman. Photo by Elizabeth Fowles.

Elizabeth Fowles, John Fowles, and Elizabeth’s daughter Anna Christy, outside Underhill Farm, Lyme Regis, Dorset, summer 1966. After difficult years without her daughter as a result of choosing Fowles over her first husband (Anna’s father), Elizabeth re-established a deep relationship with Anna through their summers at Underhill Farm. The theme of mother-daughter reunion echoes in The French Lieutenant’s Woman, which Fowles began to write soon after this photograph was taken by Fred Porter.

Elizabeth Fowles, John Fowles, and Elizabeth’s daughter Anna Christy, outside Underhill Farm, Lyme Regis, Dorset, summer 1966. After difficult years without her daughter as a result of choosing Fowles over her first husband (Anna’s father), Elizabeth re-established a deep relationship with Anna through their summers at Underhill Farm. The theme of mother-daughter reunion echoes in The French Lieutenant’s Woman, which Fowles began to write soon after this photograph was taken by Fred Porter.

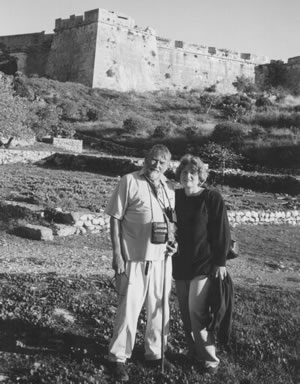

John Fowles and his biographer, Eileen Warburton, in Greece, November 1996. Warburton has been a friend to Fowles for 30 years and was given access to his unedited diaries (including those still unarchived in Fowles’s possession) and all private correspondence of his and of his first wife, Elizabeth (who died in 1990). Warburton researched Fowles’s life and work through his papers in three major archives and interviewed his friends, family, associates, and Fowles himself. Photo by Kirki Kefalea.

John Fowles and his biographer, Eileen Warburton, in Greece, November 1996. Warburton has been a friend to Fowles for 30 years and was given access to his unedited diaries (including those still unarchived in Fowles’s possession) and all private correspondence of his and of his first wife, Elizabeth (who died in 1990). Warburton researched Fowles’s life and work through his papers in three major archives and interviewed his friends, family, associates, and Fowles himself. Photo by Kirki Kefalea.